By Sandy Beauregard, and Director of Sustainability Services

The Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change mitigation adopted in 2015, aims to limit the increase in global average temperature to below 2˚C above pre-industrial levels and encourages efforts to limit warming to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels. In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”) found that limiting global warming to 1.5˚C is necessary to avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change. The AR6 Synthesis Report released by the IPCC in March 2023 warned that urgent action is needed and that emissions need to be reduced by nearly half by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5˚C and “secure a livable future for all.”

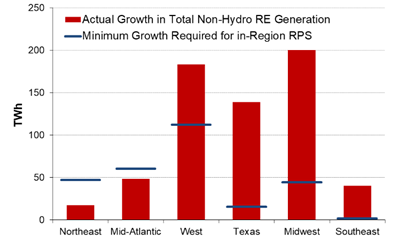

Building operations account for 30% of energy consumption and 26% of energy-related emissions globally. Addressing building energy use and emissions are a critical part of the twin paths of beneficial electrification and deep decarbonization that are required to meet emissions reduction targets. Grid decarbonization has been spurred by states ratcheting up Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) requirements. In 2022, state RPS requirements were responsible for 30% of new renewable electricity generation capacity in the U.S and approximately half of the growth since 2000. Renewable portfolio standards in 29 states and Washington D.C. now cover 58% of total retail electricity sales in the U.S. Sixteen of these RPS targets mandate at least 50% renewable electricity supply and 17 states have a 100% renewable RPS target or clean electricity standard. In the Midwest, Texas, and West, renewable electricity growth has exceeded RPS requirements, suggesting that other policies and economic factors have been the primary drivers of renewable development in these regions. In contrast, RPS policies play a more central role in renewable growth in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic where in-region renewables lag behind RPS requirements.

Growth in Non-Hydro Renewable Generation 2000-2022 by the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory

As electricity supply in the U.S becomes “greener” beneficial electrification is being used to eliminate scope 1 emissions from the transportation and building sectors. For buildings, this means electrifying the heating and cooling infrastructure to leverage the low-carbon electricity grid and eliminate fossil fuel combustion. This transition has often been driven by energy code and voluntary commitments, but with the growing urgency to address climate change we are increasingly seeing cities implement building-level energy and emissions reduction ordinances to accelerate building decarbonization within city limits.

City ordinances are evolving from their original form, benchmarking and disclosure requirements intended to bring attention to the energy consumption of large buildings, to performance requirements with enforcement mechanisms. For example, Boston implemented an early version of their Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO) in 2013 that required large buildings in Boston to report energy and water use annually. In 2021 the City amended BERDO to requires buildings to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with the goal of reaching net-zero by 2050. Similar regulations are being adopted in cities across the country including the Building Energy Use Disclosure Ordinance (BEUDO) in Boston’s neighboring city Cambridge, the Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) in Washington D.C, Local Law 97 in New York, and Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) in St. Louis. Each ordinance establishes its own timeline, goals, reporting metrics, compliance criteria, and penalties for properties that fail to achieve the mandated energy or emissions performance standard. Properties that exceed the emissions limits in New York will need to pay $268 per metric ton over the limit. In Washington D.C buildings failing to meet the energy and emissions standards will be fined $10 per square foot capped at $7.5 million. The alternative compliance payment under BERDO in Boston starts at $234 per metric ton.

These penalties essentially limit the cost of compliance but represent a significant expense and companies will certainly look to reduce emissions through more cost-effective renewable electricity purchases. A renewable energy certificate (REC) is a type of tradable certificate that represents the environmental attributes or benefits of generating electricity from renewable sources. Also known as a renewable energy credit, each REC represents the environmental attributes associated with the generation of one megawatt-hour of electricity from solar, wind, and other renewable sources. These certificates are tracked and verified by independent third-party organizations to ensure their credibility and accuracy. A company can report lower Scope 2 emissions by purchasing and retiring RECs. While there are many sources of RECs, with costs as low as $2.00 per MWh, the city ordinances generally require that any RECs used to meet the mandated emissions targets meet the same criteria as the state RPS or clean electricity standards, meaning they must come from new in-region renewable generation sources often known as Class I RECs in New England. New York’s LL97 is especially strict, only allowing RECs from renewable projects that deliver directly into the New York City grid (NYISO Zone-J).

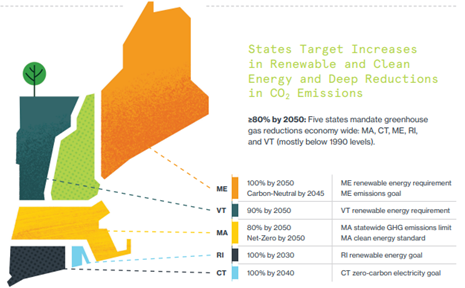

With increasing RPS requirements, looming federal policies[1], increased pressure on companies to voluntarily reduce emissions, and a growing patchwork of municipal carbon reduction regulations there may not be an adequate supply of quality RECs in the long-term and this increasing demand is likely to drive up prices. New England states have escalating RPS obligations and carbon emissions reduction targets that are expected to drive demand for RECs from New England based renewable energy generators. A primary strategy for emissions reductions is to electrify heating and transportation, which will increase the regional electric load and further drive demand for RECs to meet the RPS obligation for this larger load. The ordinances in Boston and Cambridge Massachusetts as well as Providence, Rhode Island that require emissions reductions for individual building owners are also expected to cause a notable increase in demand for in-region RECs.

Renewable and Clean Electricity Targets Across New England

As shown below, the majority of RECs in New England are expected to come from new wind projects with more than 18,000 MW of offshore wind already slated for Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and Maine. The growth of New England’s Class I REC supply will depend on the speed with which these offshore wind farms are built in the coming years. Interconnection of these wind facilities at scale requires major upgrades to the regional bulk power system. As we have seen with the New England Clean Energy Connect (NECEC) hydroelectric transmission line, these types of projects can be controversial and difficult to move forward. While the outlook for renewables in New England looks promising, there are many opportunities for progress to lag the statutory requirements. If, for example, there are significant delays in the development of wind off the coast of Maine and/or if the NECEC transmission line between Quebec and Maine that will delivery hydroelectric power into New England is not successfully developed, there may not be enough RECs available in the market to meet compliance obligations, especially if electric loads across New England grow with state-sponsored policies to advance transportation electrification and the widespread adoption of air source heat pumps.[2] If this type of compliance shortfall occurs, the voluntary market would also see a limited supply of RECs with high demand driven by the factors discussed above.

Supply of New England RECs

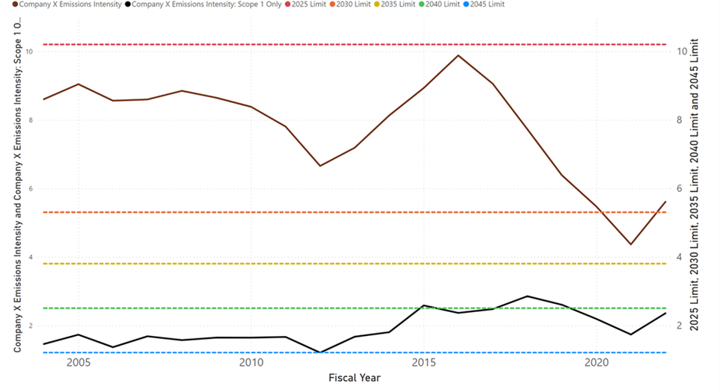

We can consider what compliance might look like for a sample company, Company X, under Boston’s BERDO emissions limits. Company X’s historical GHG emissions are below the immediate 2025 emissions threshold and plummeted below the 2030 limit during the heigh of the COVID pandemic. While emissions have since ticked back up above the 2030 threshold. Company X will not need to take any additional action to comply with its 2025 BERDO targets.

Building a comprehensive compliance strategy that considers the interplay between RPS compliance obligations, city building performance requirements, and renewable energy market trends will be critical to mitigating the financial impact. Contact an Energy Services Advisor for help understanding and navigating these complex regulations and nuanced compliance requirements.

Company X Historical Emissions Intensity Compared to BERDO Emissions Limits

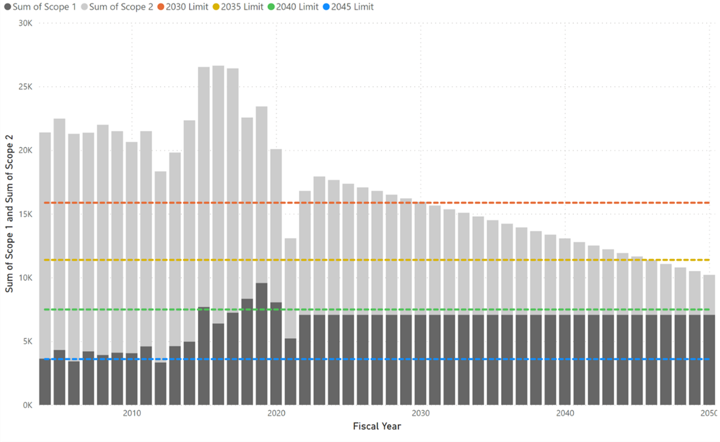

If we factor in Massachusetts RPS targets, Company X Scope 2 emissions will decline over time, bringing the company into compliance with BERDO through 2030.[1] However, as shown below, grid emissions will not decline quickly enough between 2030 and 2035 for Company X to meet its BERDO emissions limits without taking additional action.

Company X Emissions Intensity Incorporating Massachusetts RPS Compliance Compared to BERDO Emissions Limits

Focusing on Scope 2 emissions is often the most cost-effective strategy and can be achieved quickly relative to the capital planning and investment requires to implement operational and infrastructure changes that reduce Scope 1 emissions through efficiency and electrification. The initial alternative compliance payment under BERDO of $234 per MTCO2e is based on an analysis of what it would cost to address Scope 1 emissions through these infrastructure and operational improvements.

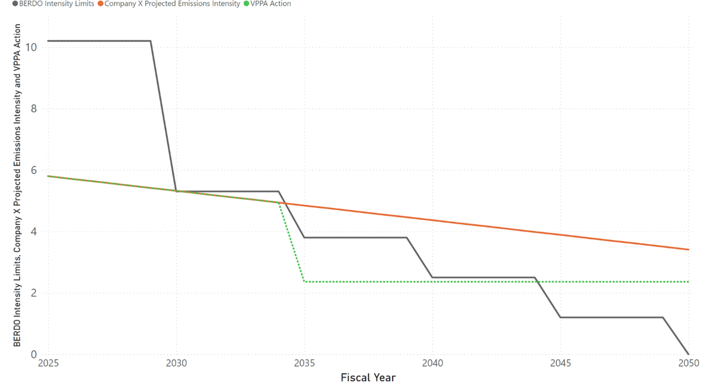

While there are many options available to purchase renewable electricity, a virtual power purchase agreement (VPPA) is most likely for large entities that need to source RECs from new, in-region renewable generators for BERDO compliance obligations. Company X would need to enter into a VPPA for a project that will come online by 2030 to maintain BERDO compliance for the following 10 years. By 2045, Company X will need to take additional action to address Scope 1 emissions to comply with BERDO.

Company X Emissions Intensity with VPPA Compared to BERDO Emissions Limits

Building a comprehensive compliance strategy that considers the interplay between RPS compliance obligations, city building performance requirements, and renewable energy market trends will be critical to mitigating the financial impact. Contact a Competitive Energy Services Advisor for help understanding and navigating these complex regulations and nuanced compliance requirements.

Photo by Bruno Abatti

(1) The Securities and Exchange Commission is expected to require publicly traded companies to provide detailed disclosures on carbon emissions and climate risk. The Biden administration has also proposed the Federal Supplier Climate Risks and Resilience Rule, which would require major Federal contractors to publicly disclose greenhouse gas emissions and climate-related financial risks and set science-based emissions reduction targets.

(2) The proposed 1,000 MW King Pine wind farm in Aroostook County and the related 1,200 MW 345 kV Aroostook Renewable Gateway transmission line being developed by LS Power is another significant project that will greatly influence the supply of RECs in the region. The wind farm and transmission line are currently scheduled to be operational in late 2029.

(3) This assumes Scope 1 emissions remain flat and the state RPS targets are achieved, despite the potential shortfall in compliance RECs discussed above.